After writing about people for the past few months, I decided to write about a place this time. The compilation post I mentioned in December will instead go up in February…maybe.

House of Comfort

Though Dunkin’ Donuts Park is fresh on the minds of Hartford residents, it is certainly not the first municipal project to run over budget and miss its targeted completion date.

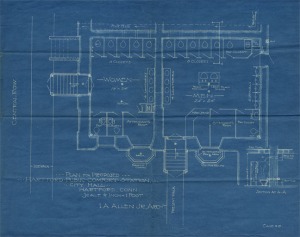

The digital collections of the Hartford History Center include a scan of blueprints for comfort stations, or houses of comfort. These were to be built at the building that was then City Hall (we now refer to it as the Old State House).

It turns out that this project took so long to complete, these initial plans were scrapped, and a different architect would ultimately draw up the plans that were used. Sometimes these were referred to as comfort stations. Most often it was house of comfort, which I use; house of public comfort; or houses of comfort, since they were building separate sections for men and women. What follows is a summary of the 19 year saga to build these facilities, gleaned from over 300 news articles. Dates of the articles I have referenced are in parentheses.

I limited my research to the Hartford Courant, so it is possible there is further documentation available about the entire process. However, as best I can tell, discussion began in 1895. At first there was talk of both a trolley waiting room and public facilities in the roadway north of City Hall (Dec 7,1895). The idea was proposed by the City Club, a non-partisan group organized in 1894 to “turn ineffective individual opinions into irresistible public opinion” (Mar 5, 1894).

Throughout the process, the City Council was generally opposed to building a waiting room. They felt that should be built by the trolley company. The idea for a house of comfort, though, received support from the very beginning (Jan 14, 1896).

Support and action were clearly not identical. Five years later the house of comfort remained unbuilt. As the discussion about a new City Hall began, talk of the house of comfort made it back into the paper (Sep 21, 1901). The house of comfort continued to be discussed for the next six months, with the appointed committee not reaching a decision (Mar 21, 1902).

In September 1903, the house of comfort committee was authorized to obtain plans from an architect (Oct 13, 1903). By January, the committee had recommended using the basement of City Hall (Jan 12, 1904). The estimated cost was $6500 (Feb 9, 1904).

And yet, it wasn’t for another two years till the location was settled (Mar 13, 1906). In May 1906, the plan was approved by the finance board. In September 1906 the Courant mentioned that Isaac Allen, Jr. drew up the plans (presumably the image shown above) “several months ago” (Sep 28, 1906).

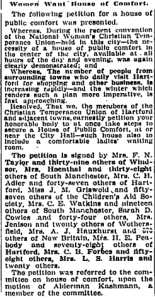

If this petition from the Women’s Christian Temperance Union is any indication, there certainly was public support for the project.

Majority and minority opinions were presented to the Board of Aldermen in December (Dec 11, 1906), and in January the project was delayed again so they could confer with Consolidated Railway Company about a combined project (Jan 15, 1907).

By 1910, the estimated cost was up to $25,000. This went to a citywide vote in April 1911 (Dec 13, 1910), and it passed (April 5, 1911). It would still be another three years until the house of comfort would open. Former City Engineer F. L. Ford wrote a paper about houses of comfort in general. Per the Courant, “It would appear from the information given, that Hartford is decidedly slow in taking up this question” (Aug 17, 1911). That seems to be a fairly accurate statement!

The next hurdle came from the United States government. A suit was brought against the city due to the proposed location. In essence, they thought the house of comfort would negatively effect the adjacent post office (Sep 13, 1911).

A competition was announced in September, with an October deadline, to design the house of comfort. Only Hartford architects would be considered (Sep 22, 1911). Few designs were submitted, and ultimately Smith and Bassette were selected to perform the work (Oct 25, 1911). It was not until January 1913 that the government dropped their lawsuit and construction could get underway (Jan 29, 1913).

Of course, it couldn’t be that simple. One last time, the city debated the location (Feb 22, 1913). Again, they were contemplating whether to use the rear of City Hall, or build a structure on State Street that would incorporate a trolley waiting area. Finally the rear of City Hall was firmly selected, primarily because switching the site would require another citywide vote and sticking with the original plan was the easier option (Mar 1, 1913).

The contract was drawn up with the architects (May 21, 1913), and the project went out to bid. An unforeseen issue was that no contractors actually submitted any bids (July 16, 1913). Two weeks later they had received three, but they all came in too high (July 30, 1913). A committee met to pare down the plans so that both the architects’ fees and the contractors’ fees would be under the $25,000 limit. After another round of bidding, Don O’Connor won the contract. O’Connor was supposed to be finished within two months of signing the contract (Sep 10, 1913).

As construction progressed, numerous items were found in the area. These included a brick vault (Sep 25, 1913) and an old walking staff (Oct 8, 1913). It seems that so many items were being uncovered, someone thought it would be a good idea to put them on permanent display.

I did not find any indication that this was ever seriously considered.

During construction, the contractor, Don O’Connor, discovered that the walls of City Hall needed to be reinforced. O’Connor went ahead with this extra work, which entailed using 43 yards of concrete, without notifying the city plan commission and the city building committee. This unauthorized, extra expense ruffled some feathers (Nov 26, 1913).

For a while it was looking as though the house of comfort would be ready to open January 1, 1914 (Dec 7, 1913). There were a few more ‘extras’ added to the plan, including a realignment of the fresh air pipe (Jan 7, 1914), and a water regulator and safety valve for the new boiler (Feb 18, 1914). Accompanying the extras was squabbling over the costs.

Finally, on May 30, 1914, the house of comfort in City Hall opened for business. There were no formal ceremonies. The women’s side was open Monday – Saturday, 8:00AM – midnight, and 10:00AM – 10:00PM on Sunday. Their attendants, Mrs. Bridget Martin and Mrs. James J. Moran, were to be paid $730 annually. On the men’s side, the hours were 8:00AM-midnight, daily. Attendants John J. O’Connell and James J. Morrison were to be paid $1000 (May 29,1914). The facilities proved so popular that six years later they were discussing an expansion. Each week 28,000 people were taking advantage of the service (Feb 10,1920).

The facilities lasted for 56 years, closing in 1970 (Apr 27,1983). When the Old State House was renovated in 1979, they were completely removed (Nov 20,1985).

I’m sure we could find many similar stories, of projects spanning two decades and repeatedly debating the same issues. This one just happened to have evidence in the archives.

The Box: Blueprint for comfort stations (restrooms) at City Hall, Hartford. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library. hpl_hhc_ca1_b358_waitingstation010.jpg

Other Sources: Ok, I know this is bad form, but in the interest of getting this posted, I am not going to list the titles of the articles I read. I have, as previously mentioned, provided the dates. If you have a Connecticut library card, you have access to the historic Hartford Courant online database. I’m happy to explain further how to find it. Here is a screenshot of my search:

If you access the database through the State Library, this will search through 1922 and yield 248 results. West Hartford (and other towns) provides access to 1923 – 1990, increasing the results to 301. Either way, you may sort the results by date.

Caroline Hewins

I am squeezing in my Hartford Outside the Box entry for December right under the wire. I didn’t visit any new archives this month. I haven’t been able to write about all the documents I’ve seen over the past few months, so this is a bit of a compilation. January will be the same.

Caroline Hewins was a fixture in Hartford for many years. A native of Roxbury, MA, she came to the city in 1875 to be the librarian at the Young Men’s Institute, one of the organizations that would later combine to form the Hartford Public Library (HPL). Hewins continued to work at the library until her death in 1926. As her job changed from providing services at at private subscription library to a free public library, much of her work focused on providing resources to the city’s children.

Hewins’ dedication to youth could not be contained within the walls of a library. For 12 years she lived at the North Street Settlement House, where she set up HPL’s first branch library. She would take children on excursions, and would speak about children’s books to organizations.

![Meeting minutes, December 6, 1909. [1]](https://cyclingarchivist.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/img_0415.jpg?w=300&h=212)

The letters sent to the Days illustrate the ease with which Hewins interacted with children and truly cared for their well being. In an undated letter, Moro “wrote” to Katharine Day after Hewins and the dog had visited and not seen Katharine. Katharine was sick, so Moro related some of his own recent illnesses in sympathy. Moro also discussed how he prefers playing with the street dogs in his neighborhood, but his aunties prefer him to play with cleaner pets. Additionally, Moro is excited to be traveling soon to Boston, via train[2]. The letter is written at a level a young child could certainly understand and appreciate.

Another letter was written by one animal to another. Rabbits dwelling with the Days had recently lost two of their offspring. Moro wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Rabbit to comfort them; though more than likely, Moro/Hewins’ intent was to inject some humor into the situation and assure Katharine and Alice that the disappearance was not their fault[3].

![Undated letter to Katharine and Alice Day[4]](https://cyclingarchivist.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/img_0571.jpg?w=300&h=81)

In addition to letter writing, one of the ways Hewins demonstrated her commitment to the young people in her community was with the creation of a scholarship. The scholarship was established in 1926. Hewins wrote about the scholarship, “I have seen in all these years girls who would have been good librarians for children, but could not afford the training, and this will help them to fit themselves for positions that are open for them.[5]” Among those contributing to the fund was Louise H. Seaman of Macmillan [Publishing] Co. She called the scholarship, “one of the most stirring tributes I have ever heard planned.[6]”

Whether touring around the city, writing letters, or establishing a scholarship, Caroline Hewins consistently found ways to connect with the young people of Hartford and beyond, and to brighten their lives. Rev. Dr. Rockwell Harmon Potter, of Center Church, officiated at her funeral. His words were quoted in the Hartford Courant.

“She lived in a beautiful world,” he said, “where in her works and travels she had visited the beautiful parts of the earth and had read of the beautiful deeds of life. Children romped to meet her at her call, laughed at her stories, and were made wise by her counsel and advice.[7]

Hewins was well known in library organizations, including the American Library Association and the Connecticut Library Association. According to the Courant, tributes were sent from many places, including New York, Ohio, and Washington, DC.

The Box: Katharine S. Day Collection, Caroline M. Hewins letters, multiple dates. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Other Sources:

Connecticut State Library, Record Group 107, Records of the Hartford Woman’s Club, Minutes of meetings, 1896 February 3 – 1918 April 25, Box 1.

City History Club Notebooks, 1910, MS 75764. Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, Connecticut.

[1] Connecticut State Library, Record Group 107, Records of the Hartford Woman’s Club, Minutes of meetings, 1896 February 3 – 1918 April 25, Box 1.

[2] Katharine S. Day Collection, Caroline M. Hewins letter to Katharine Seymour Day, [1870-1887] n.d. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

[3] Katharine S. Day Collection, Caroline M. Hewins letter to Katharine Seymour Day and Alice (Day) Jackson, [1870-1887] n.d. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

[4] Katharine S. Day Collection, Caroline M. Hewins letter to Katharine Seymour Day and Alice (Day) Jackson, [1870-1887] n.d. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

[5] Katharine S. Day Collection, Caroline M. Hewins letter to Alice (Hooker) Day, 1926 January 28. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

[6]“Hewins Fund is ‘Stirring Tribute’,” Hartford Courant, February 22, 1926.

[7]“Final Tribute Offered to Miss Hewins,” Hartford Courant, November 7, 1926.

Harriet Jacobs Letter

I took a break from this series for the month of October, having used my writing energy to share my thoughts with the SNAP Roundtable about networking.

The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center Library is located in the Katharine Seymour Day house at Nook Farm in Hartford. I previously visited the library about a dozen years ago. While taking an architectural history grad course at Trinity College, I used blueprints held by the Stowe Center to write a paper about the Rossia Insurance Company building. The building stood on the corner of Broad St. and Farmington Ave., the current location of the YWCA. I remember it as being my first time researching with primary materials, and that it put the idea of studying archives into my head. For that reason, I was excited to return and view more material.

There is much less information available online about the Stowe Center holdings than the other collections I have written about. I chose what I wanted to view from a list of women’s history materials. When I arrived, I had to search through the card catalog (yes, actual cards) to find the specific items. Certainly it would be great if this information were online, but there’s something to be said for Amazon and Google not knowing what I searched for.

As I looked over the list of materials, I recognized Harriet Jacobs’ name. A copy of her memoir, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, is among the texts I have had (and schlepped around the country) since an undergraduate history class. In the introduction, editor Jean Fagan Yellin discusses the process Jacobs went through as she debated whether to have her story published, and how. One option was to have Harriet Beecher Stowe assist with the writing. There was even a discussion of Jacobs’ daughter traveling with Stowe to England, with the hope of meeting potential publishers. When neither of these came to fruition, Jacobs decided to write it herself[1].

Yellin implied that the two women never corresponded directly, so I was not at all surprised when I found that Jacobs’ letter was not addressed to Stowe. This letter, dated February 10, 1865, was written to abolitionist Samuel Joseph May. May had sent a pair of spectacles to Polly Mason, which were delivered by Jacobs. Jacobs was writing to convey Mason’s thanks, as well as to share stories about Mason’s life, and the work that Jacobs was doing in Alexandria, Virginia.

Jacobs paints a vivid picture of life for freed men and women in the Washington, DC area during the winter of 1865. Miss Mason was a white woman. Her brother had had a son, William, with a colored woman (the term Jacobs uses), and Miss Mason was living with William, his mother, and two children in a small cabin. She had received a stipend from what Jacobs calls “our Society of friends in New York” to help her through the winter, and having the spectacles was allowing her to support herself once again by sewing.

Additionally, Jacobs wrote about the lack of clothing, food, and fuel. A grocery store owner wasn’t selling food one day because his baby had died. The government was helping somewhat, having provided a thousand blankets and two hundred cords of wood. Per Jacobs, though, there were over five hundred destitute families.

Despite the hardships she was witnessing, Jacobs wrote with delight about encountering the 111th Ohio Regiment at L’Ouverture Hospital. “What a picture. the old Slave pen within an arms length. the Colored Soldiers behind me, the white Soldiers in front. two Ladies by my side so deeply interested.” As she continued writing, however, she decided there could be an even better day.

![Katharine S. Day Collection, Harriet Jacobs letter to Samuel Joseph May, [1865] February 10. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, CT.](https://cyclingarchivist.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/img_0564-1024x411.jpg?w=300&h=120)

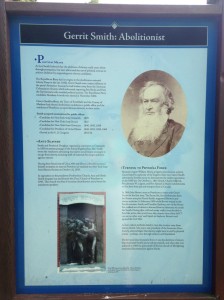

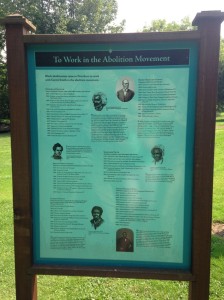

As I read Jacobs’ letter, and was trying to decide which direction I wanted to take this blog post, I was reminded of my visit this summer to the Gerrit Smith Estate in Peterboro, NY. Smith was a philanthropist and abolitionist. A sign on display at the estate describes Smith’s interactions with Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, and others. Had Smith and Jacobs met? With my limited research, I don’t have any proof that they did. Smith is, though mentioned in a footnote in Incidents. Jacobs’ daughter, Louisa Matilda, studied at Hiram Kellogg’s Young Ladies’ Domestic Seminary in Clinton, NY. Per the footnote, Louisa’s tuition and fees were reduced. Kellogg did this for other black students, too; he paid a portion, and the remainder was covered by Smith[2].

There is a greater chance that Smith met Jacobs’ brother. It was John S. Jacobs’ idea for his niece to attend Kellogg’s school. John Jacobs brought Louisa to Clinton, and then continued on to Rochester. There he worked with Frederick Douglass, including lecturing with him in the area near Smith’s home[3].

Smith certainly knew of Harriet Jacobs, even if they never met. A footnote in a paper by Kate Culkin states that Lydia Maria Child wrote to Smith, discussing Harriet Jacobs’ book. In Harriet Jacobs: A Life, Yellin relates a letter from Susan B. Anthony to Smith that mentions paying travel expenses (related to suffrage work) for Louisa Jacobs. Anthony reminds Smith that Louisa is Harriet’s daughter[4].

As I continued my research online, I found a letter written by Harriet Beecher Stowe to Gerrit Smith. To me, this brought everything full circle. The key players in the abolition movement all seemed to know, or know of, each other. So while this one letter by Harriet Jacobs does not have a specific Hartford angle, all the various directions it can lead you demonstrate how central longtime-Hartford resident Harriet Beecher Stowe was to the conversation.

This was only one letter, but there are countless others at the Stowe Center waiting to be read again. The Center’s manuscripts and other materials cover a variety of topics. I only live a mile away; I wish I had more time to research!

The Box: Katharine S. Day Collection, Harriet Jacobs letter to Samuel Joseph May, [1865] February 10. Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, Hartford, Connecticut.

Other Sources:

Peterboro, NY is also home to the National Abolition Hall of Fame and Museum.

[1] Harriet A. Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, ed. Jean Fagan Yellin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987), xviii-xix.

[2] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents, 289n1.

[3] Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A life ([New York]: Basic Civitas Books, 2004), 98-99.

[4] Jean Yellin, Life, 204.

H[amilton] Outside the Box: Diaries of Eliza Eaton

My birthday falls this month, and as a treat to myself, we are going 200 miles outside of Hartford for the Outside the Box series.

As an undergraduate at Colgate University, I pretty much had no idea what special collections and archives were. I knew there was a door labeled with this, at the end of a hallway as I climbed the stairs to my preferred study area*. I might have peaked in once, but that was the extent of my interaction with Colgate Special Collections and University Archives. Seventeen years after graduating, and eight years after finishing my graduate degree in archives, I decided it was time to change that.

If you have read the other entries in this series, it probably won’t surprise you that I chose to look at the diaries of Eliza Eaton. The last name was familiar to me, but otherwise I didn’t know anything about Mrs. Eaton. Some of the diaries were from when her husband was President of the University. I was curious what sort of interaction she might have had with the students, and what she might have to say about life in Hamilton over 130 years before I arrived in town.

As it turns out, she really didn’t have much interaction with the students. At least, not much that she wrote about in 1860. This probably isn’t too surprising. I don’t think I had any interaction with the President’s wife while I was a student, either.

Many of Mrs. Eaton’s notes are about attending church, calling on friends, and the comings and goings of family members. One of the longest entries was from the beginning of the year. On January 2, 1860, Mrs. Eaton stopped at the Spear’s house to invite Mrs. Spear to dine with her the next day. She covered two full pages writing about the encounter. The handwriting is a bit difficult (even as someone who reads cursive well!), but as I understand it, there was a disagreement between Mrs. Eaton and Professor Spear. When Mrs. Eaton stopped by that day, Mrs. Spear attempted to smooth things over by offering Mrs. Eaton a barrel of flour. Mrs. Eaton wrote that she, “could not accept a [barrel] of flour in lieu of an apology for insult received.[1]” This, it seems, added fuel to the proverbial fire. I’m still not entirely sure I understand exactly what happened, but it certainly had me hooked to continue reading through the volume.

There are a couple of indications that Mrs. Eaton wrote about happenings after the fact, or went back and updated entries after some time had passed. On Thursday, January 12, for example, the first and last sentences on the page are fairly identical. At the top of the page she wrote,

Scandalous handbills put under the plates at the Boarding Hall, & put up in the village warning the Ladies from associating with the students on account of a distemper that some four of our best students have got Prairie Itch. I hope the authors will be found out &, if students, expelled.

After writing about attending an event at the Baptist Church, Mrs. Eaton concludes the entry with, “This morning, printed handbills were found under the plates at the Boarding Hall.” It seems like it could easily have been a note so that she would remember to go back and fill in the details at a later time. Additionally, on Tuesday, November 6, Mrs. Eaton noted Abraham Lincoln’s election to the presidency. I don’t think Abe himself found out that quickly! In the entry for February 6, she describes meeting a three month old baby, and then notes in parentheses that the baby died three weeks later. Regardless, she certainly relates some of the more unusual happenings in town.

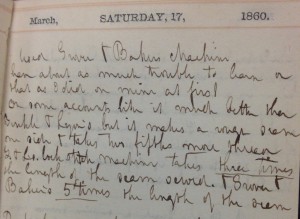

Though the stories of feuds and scandalous handbills are entertaining, there is another story thread (pun intended) that weaves its way through this volume: the purchase of a sewing machine. On Friday, January 13, Mrs. Eaton “Walked to the village. Called to see the agent in regard to Sloats Sewing machine.” On the 24th, she visited three ladies to see three different machines – a Sloat, a Singer, and an Eagle. Unfortunately, she did not describe the experience. Her research fairly complete, Mrs. Eaton sent off $37.50 for a Finkles and Lion Sewing Machine on February 2. It arrived nine days later. She kept her feelings on the matter to a minimum. “I like it.[2]” A few days after that she made a shirt for her husband and found “it requires much patience & perseverance to learn to regulate the machine.[3]” On March 16, she exchanged the machine for one week, to try out a Grover and Baker. That brought its own learning curve, and apparently it also used a lot of thread.

Soon, Mrs. Eaton decided the Grover and Baker wasn’t so great after all, and she looked forward to the return of her Finkles and Lion. I was intrigued by the next comment. ” ‘Mrs. Ashton’ [sic] must have been a wonderful woman. I wonder where Grover and Baker found her! Barnum should be after her.[4]” When I stopped laughing at the mention of P.T. Barnum, I did a quick Google search, and immediately found what Mrs. Eaton was referring to (I recommend the PDF view). Finkles and Lion had written a great story about how Mrs. Aston was bogged down with her sewing, until her husband saved the day by buying her a sewing machine. In short, advertising practices have changed little in the past 155 years!

There is much from this volume that I have not related, and it is the earliest of the 23 held by SCUA. I took a quick look at a couple of the later volumes, and found that her handwriting became more difficult to read. Understandably, she also seemed unhappy in the years after her husband died. Still, any of these volumes would make a great research project, for a current Colgate student or anyone else.

One of the aspects about archives that I love, is that you never know where your research will take you. I picked up Eliza Eaton’s diaries thinking I might learn more about town and gown relations. Instead, I learned about the purchase of a sewing machine. If there are any Colgate students reading this, I encourage you to make use of the wonderful resources in SCUA. They have a variety of material (see links on right side of page under “Collections”) and I guarantee you will learn something new about Colgate, the Village of Hamilton, and people from their past.

Archives and special collections are common to colleges and universities, including those closer to Hartford than Colgate is. Many welcome visitors, too. Find one, visit, and learn!

The Box: Diary (1860), A1137, Eliza Eaton diaries, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University Libraries.

[1] All quotes are from Eliza Eaton’s 1860 diary.

[2] February 11, 1860

[3] February 15, 1860

[4] March 22, 1860

Curious about researching at Colgate’s SCUA? They have a great intro video.

*A few years ago the library underwent an expansion and renovation. SCUA is now in a different location.

A Little Farther Outside the Box (Or what you can find in University Archives)

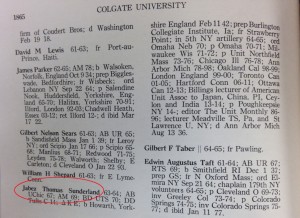

Last month I wrote about Eliza Read Sunderland, wife of Rev. Jabez T. Sunderland. As I researched Eliza in the Hartford Courant, I found an article about Rev. Sunderland that mentioned he had attended Colgate University. As a Colgate grad, and having previously worked with a collection about the Sunderlands, I was surprised I had not previously known this.

While up at Colgate last week to research in the Special Collections and University Archives, I asked if they had any information about Rev. Sunderland. In fact, they did! There were two pieces of information available. The first was his entry in the General Catalogue, a listing of all students (regardless of whether they graduated) from the early years of the school.

Additionally, the archives holds his record from the alumni office. From both of these pieces we learn that Rev. Sunderland entered Colgate as a member of the class of 1865.

He left to serve in the Civil War, and later continued his studies elsewhere (it was not until after World War II that finishing a degree became more common than not).

This, my non-archivist friends, is the magic held by college and university archives. It is all available, you just have to ask.

(Special thanks to Allyson Smally, Colgate’s Processing Archivist)

Eliza Read Sunderland

Below is the second post in my series on archives in Hartford. I intend to post monthly, for a year, highlighting primary sources and some of the stories they tell. Please see my series introduction for more information.

In August 2005 I sold my condo, left my insurance company job, and moved from Connecticut to Michigan to begin graduate school. Sometime in the next couple of months, I found the papers of Eliza Read Sunderland at the University of Michigan’s Bentley Historical Library. After living for many years in Ann Arbor, Mrs. Sunderland and her husband moved to…Hartford! I had moved 700 miles away, and managed to find the papers of a woman who spent her final years living on Oxford Street in Hartford’s West End. I no longer remember how I came upon the collection, but I was excited enough that I wrote a paper about it that semester, and another one during my final semester. Re-reading the second paper, I found that I had wondered which libraries and archives in the Hartford area would have collections that would add to my understanding of Eliza Sunderland.

It’s not that I have ever forgotten about Mrs. Sunderland, but she was not in the forefront of my mind as I prepared to examine the records of the Hartford Woman’s Club at the Connecticut State Library. Convenience is proving to be a major factor in how I choose which archives to visit, and which collection to highlight. The Connecticut State Library is open on Saturdays, and is free. Additionally, they have a number of finding aids (guides to the collections) available online. So my decision was based more on what I would find and when I could find it, rather than who I would find.

Finding aids, as this one did, are meant to give you a general idea what you will find in a collection. Few written these days will detail all of a collection’s contents. While I knew I would find meeting minutes, I did not know for sure I would also find membership lists. The original membership list, from the club’s founding as the Motherhood Section of the Sociological Club of Hartford, Conn., caught my eye particularly because of the marginalia, but also because of familiar Hartford names.

It is interesting to see not just who had how many children, but also in which neighborhoods the women lived, where they lived in relation to each other, and occasionally, if they had moved. Melvin and Edward T. Hapgood were cousins and architects, whose wives were both members. At another time I wrote a paper about one of Edward T. Hapgood’s buildings, the Rossia Insurance Company, that stood at Farmington and Broad.

One point that needs to be articulated is that at the time the club was formed, most woman’s clubs were not focusing on motherhood. They were being formed by women whose child rearing days were over; women who were ready to expand their own horizons. In forming the Motherhood Club, though, these Hartford women did so specifically to help them better their children’s lives. In some respects it was a forerunner to today’s Parent Teacher Organizations. Over the years, though, the name of the club was changed; in 1921 it became the Hartford Woman’s Club. I was gearing up to write about the above (and may still in a future post), when I first found a reference to Mrs. Sunderland. In the 1908-1909 calendar, she was listed to give a speech on April 19, 1909.

A write-up of her talk was published in the Courant the next day, and was included with the meeting minutes.

There is so much that can be written about this collection, it seems odd for me to go on a tangent about a woman who was a relatively small part of the organization. However, during her short time in Hartford, Mrs. Sunderland had a sizable impact.

Born in Huntsville, IL in 1839, Eliza Jane Read was the daughter of Amasa and Jane Henderson Read. After graduating from Mount Holyoke Seminary, Eliza subsequently received a bachelor’s degree, and a Ph.D. in philosophy, from the University of Michigan. She taught both before her marriage and after, including at high schools in Chicago and Ann Arbor, as well as serving as Principal of a high school in Aurora, IL. Eliza and Jabez Sunderland were married in 1871. The Sunderlands lived in Milwaukee, WI, Northfield, MA, Chicago, IL, Ann Arbor, MI, and Toronto, Ontario, Canada prior to moving to Hartford, CT in 1906.

Two of her accomplishments were serving on the Hartford Board of School Visitors and speaking before the State Legislature. In 1908, years before the passage of woman suffrage, Eliza was elected as a School Visitor. A petition, bearing the signatures of men and women of Hartford, was presented to the city’s Republican committee as they debated that year’s slate of candidates. Newspaper reports tell of some discussion, but ultimately Eliza was nominated for a position. An article in the Hartford Courant stated that Eliza was “well fitted for the place on account of her lifelong interest in school matters, her experience as a teacher and her intellectual training.” After discussing many of Eliza’s accomplishments, the articled concluded, “if Mrs. Sunderland is elected, the new board will have upon it a woman whose career has given her the equipment needed for the work”[1]. Eliza was a historian of the educational system of the United States, often relating a series of events from the Plymouth Rock and Harvard College to the birth of the public schools for boys and, later on, girls. In her speeches she frequently listed the years in which women were finally admitted to various universities. Additionally, she spoke more than once on the contemporary condition of the American public schools. These are some of the accomplishments to which the Courant referred, and likely ones that led to Eliza’s appointment to the textbook committee once on the Board.

In March 1909 Eliza spoke in front of a Connecticut legislative committee considering giving women the vote. She provided several reasons why women deserved “this right guranteed [sic] to all citizens of a Republic.” These reasons included the fact that women “are descendents from the Revolutionary foremothers who did their full share in winning American Independence, and founding a nation.” She also pointed to the contributions women made to the Civil War effort, the need to “save themselves from the unjust man made laws under which [women] have so long lived,” and “the affect [voting] will have upon their own character, in developing an all around complete woman-hood”[2].

Sadly, it was a year later, March 1910, that Eliza Read Sunderland passed away. The Motherhood Club sent flowers, and at the meeting on April 4, the minutes state that “a card of appreciation was read from Rev. J.T. Sunderland acknowledging the tribute of flowers received”[3].

Research in archives is about making connections. Clearly I found a connection between collections (and the people they represent) in Ann Arbor and Hartford. As I read more Courant articles about Jabez and Eliza Sunderland, I found out that Jabez briefly attended Colgate University [4]. Another connection to my past!

There are many other connections waiting to be found in the records of the Hartford Woman’s Club. It is a great collection for anyone researching women’s issues in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I hope to revisit it in the future.

The Box:

Connecticut State Library, Record Group 107, Records of the Hartford Woman’s Club, Minutes of meetings, 1896 February 3 – 1918 April 25, Box 1.

Other Sources:

[1] “Mrs. Sunderland Born in the West: Career of Nominee for the School Board,” Hartford Courant, Mar 20, 1908.

[2]“Some Reasons Why Women Should Have the Vote,” Box 4, Eliza Sunderland Papers, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

The information about Eliza Read Sunderland was researched while I was a student at the University of Michigan, 2005-2007.

[3] Connecticut State Library, Record Group 107, Records of the Hartford Woman’s Club, Minutes of meetings, 1896 February 3 – 1918 April 25, Box 1.

[4]“Unity Church Pastor Resigns,” Hartford Courant, Feb 25, 1911.

Music in Bushnell Park

Below is the first post in my series on archives in Hartford. I intend to post monthly, for a year, highlighting primary sources and some of the stories they tell. Please see my series introduction for more information.

[T]he community that hath no music in its soul falls far short of its possible best. And in bad times or bright, music may be not only an expression of its varied emotions, but also a means for maintaining at high level, its community spirit.

~ Rev. Dr. Robbins W. Barstow

Hartford has music in its soul. At this time of year there is plenty of live music to be heard in Bushnell Park. Monday Night Jazz is always a big hit, as is the Greater Hartford Jazz Festival. There are probably other events that haven’t made it to my radar screen.

While trying to find my first document to write about for this series, I looked at the finding aid for the Hartford City Parks collection (held by the Hartford History Center at the Hartford Public Library), and found a speech listed, given by Rev. Dr. Robbins W. Barstow. President of the Hartford Seminary Foundation and a member of the Board of Park Commissioners, Barstow was the master of ceremonies at the opening of the Bushnell Park Music Shell in September 1935. I knew the current pavilion did not date to 1935, but did not know anything more about the situation. Unlike many other structures that have been torn down, no marker notes the shell’s location.

The three-paged speech was typed, double-spaced, with a few handwritten corrections. Rev. Barstow’s name was written on it, probably at a later date.

While I initially intended to write about the speech itself, I soon found it sending me in several different directions, learning plenty about this former piece of the Hartford landscape.

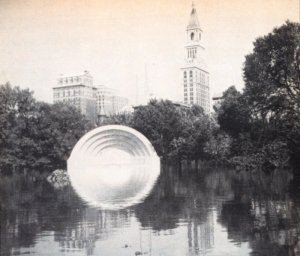

Located in the eastern portion of the park, the construction of the shell was a Federal Emergency Relief Administration (soon to become Works Progress Administration) project, and appears to have first been mentioned in the Hartford Courant in June, a mere three months before it opened.

The intention was to build a “stage with acoustical properties, on which 60 musicians might be seated, and on which it would be possible to present a pageant or theatrical offerings[1].” The dimensions were to be 22 by 65 feet, with a radius of 32 feet for the shell. FERA would provide $6000. A month later the permit had been filed, estimating the cost at $9139.09. This was $5292.20 for labor and $3846.89 for materials[2].

The final product, as reported by the Courant, was

70 feet long, 35 feet high and 30 feet deep with five concentric overlapping sounding boards. It is copper lined wood on a concrete base, and between the wainscotting and sounding boards is an indirect lighting system that reflects the rays of the 180 100-watt bulbs similar to the projection of the sound waves. The lighting system makes it possible for any one in the audience to easily read a program during an evening performance[3].

The Hartford Times provided a detailed description of the colors.

The outside is fawn grey, with a copper roof which will be washed with vinegar to turn it a soft green, and the inside is a pale putty green. The green was decided on experimentally, as meeting the requirements, not too much white, not blue or turquoise, or any warm tone as buff or yellow. The problem was not primarily one of appearance, but to get a color which will not hurt the eyes of the audience when the light from the 180 100-watt lamps is reflected to the far end of the park[4].

It’s too bad the newspaper photographs were all in black and white.

At the music shell’s inaugural concert, Barstow spoke of Hartford’s love of music, both at outdoor events and indoor. Additionally, he complimented the shell and its “marriage of technical engineering skill and true musical appreciation and passion[5].” The other speakers Barstow introduced were Mayor J. Watson Beach, Park Commissioner Frances Goodwin II, and the project’s architect, Harold F. Kellogg. The men spoke to an overflowing crowd; all 4000 chairs were occupied, and many people were standing.

The stage was the brainchild of Commissioner Goodwin, who felt the orchestra concerts the previous summer had been “marred by lack of proper acoustical presentation.” It was designed by the team responsible for similar projects in Hollywood, Boston, and New York, MIT Professor W.R. Barss and architect Kellogg. The completed shell had seating for 70 musicians (20 more than in Boston!) and, per the Courant, “The design incorporates the most advanced principles of acoustical engineering and permits a fine violin note to be heard at 1000 feet.[6]”

In closing, Barstow noted that everyone had gathered primarily to hear the Hartford Civic Symphony Orchestra perform. He then introduced director Angelo Coniglione and harpist Salvatore de Stefano. Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro was the first selection, followed by Zabel’s harp concerto, and finally Cesar Franck’s Symphony in D Major[7].

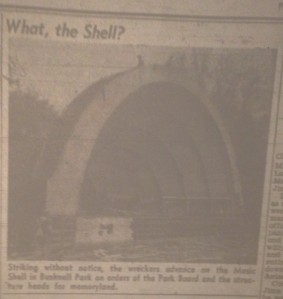

Over the next few years, the stage was damaged by several storms, including the flooding that accompanied the Hurricane of 1938.

However, it was a surprise when, ten years after being built, the shell was torn down. The Hartford Times expressed this sentiment with the photo caption, “What, the Shell?[8]” The president of the Park Board at the time, Newton Brainard, told the Courant the shell “is not in good shape and doesn’t fit in with the board’s plans for reconstruction of the park.” In complete contrast to the laudatory statements of 1935, Brainard informed the newspaper that the shell was a temporary structure, “and had no beauty.[9]” When the shell’s destruction was mentioned in the Board of Park Commissioners’ Annual Report, it was recorded that, “It was necessary to tear down the music shell in Bushnell Park as the sills were becoming unsafe and it was impossible, due to the intricate construction, to make adequate repairs to withstand the wind pressure.[10]” It is interesting to note that this was the Report for the year ending March 1947, over a year after it came down.

Over the years there were additional temporary structures, but nothing permanent until the current Performance Pavilion was built, on the west side of the park, in 1995. Articles about that structure may be found in the Courant. I encourage anyone who is interested in this topic to seek out the resources listed below. I encountered numerous trivia facts that, while out of scope for this post, were incredibly interesting in their own way.

The Box: “Address at the Opening of the Music Shell, Bushnell Park,” Hartford City Parks Collection, Box 1, Folder 22. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

The Annual Reports of the Park Commissioners are also held by the History Center, though are not listed in the finding aid.

Curious about researching in the HHC? Here is a series of blog posts: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

Other Sources: Hartford’s daily morning paper, The Hartford Courant, is available online through local libraries. The microfilm is also available. The Hartford Times was an afternoon paper that ceased publication in 1976. While it has been microfilmed, it is not available online. The microfilm is not as readily available as the Courant‘s, but is open for research at Hartford Public Library.

[1] “Music Shell Favored For Bushnell Park,” Hartford Courant, Jun 6, 1935.

[2] “Music Shell Cost As FERA Project Set At $9139.09,” Hartford Courant, Jul 3, 1935.

[3] “New Music Shell In Bushnell Park To Be Dedicated This Afternoon,” Hartford Courant, Sep 29, 1935.

[4] “First Concert Tomorrow in Bushnell Park,” Hartford Times, Sep 28, 1935.

[5] “Address at the Opening of the Music Shell, Bushnell Park,” Hartford City Parks Collection, Box 1, Folder 22. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

[6] “First Music Shell Event Next Sunday,” Hartford Courant, Sep 23, 1935.

[7] The musical program is mentioned in several Courant articles, as well as in the Hartford Times.

[8] “What, the Shell?” Hartford Times, Apr 25, 1945.

[9] “Park Music Shell To Be Dismantled,” Hartford Courant, Apr 26, 1945.

[10] “Eighty-seventh Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners,” Hartford City Parks Collection, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library, Hartford, Connecticut.

Series Introduction

Throughout the world, there are many great libraries and archives, housing some fabulous (and, to be honest, some mundane) papers and records. The collections held by Hartford area repositories are no exception. In our capital city alone, we have Hartford Public Library, the Wadsworth Atheneum, the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, the Watkinson Library at Trinity College, the Connecticut Historical Society, and the Connecticut State Library (I may have even left out one or two). A little farther down the road, you can find others, such as the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Hartford and the Hill-Stead Museum.

As I mentioned in January, I miss writing about collections. With that in mind, I am starting a year long project (July 2015 – June 2016) to learn and teach about Hartford stories through manuscripts. I have not completely decided which repositories I will visit, or even if I will visit more than two or three. As with many things in archives, it depends.

I have chosen to call this series “Hartford Outside of the Box,” referring to the boxes in which archivists and records managers keep collections, as well as the fact I don’t plan to focus on the most familiar people and places. The subjects I write about will reflect my own interests. Posts about people, for example, are likely to focus on women. Obviously, I will also be limited to what has been collected.

Archival boxes are necessary for the preservation of the material. Every now and then, however, the material needs to come out of the box and get some academic exercise. My hope is that all who read this blog will gain a better understanding of what is available in local archives; possibly be inspired to visit, support, and further learn from the organizations; and gain a few tidbits of information about the city in which we live.

Look for the first post mid-July!